The interviewer asked, “Eighty-one years is a long time. As you enter your final season of life, what would you like to say to younger Christians who are itchy for a deeper and more authentic discipleship? What’s your word to them?”

Eugene’s response was, “Go to the nearest smallest church and commit yourself to being there for 6 months. If it doesn’t work out, find somewhere else. But don’t look for programs, don’t look for entertainment, and don’t look for a great preacher. A Christian congregation is not a glamorous place, not a romantic place. That’s what I always told people. If people were leaving my congregation to go to another place of work, I’d say, “The smallest church, the closest church, and stay there for 6 months.” Sometimes it doesn’t work. Some pastors are just incompetent. And some are flat out bad. So I don’t think that’s the answer to everything, but it’s a better place to start than going to the one with all the programs, the glitz, all that stuff.” (http://jonathanmerritt.religionnews.com/2013/09/27/faithful-end-interview-eugene-peterson/)

Frankly, this was the exact opposite of what I expected Eugene Peterson to say. His work resonates really well with Bible readers in this day and age and much of that is because of his ability to listen to the voices and needs of peoples in the pews. Based on my own encounters of those who read his work, I had assumed that he would say something more like, “Find a church that really meets your needs and encourages you to follow Christ as you are”. But he didn’t. Instead, he said, “Go to the nearest smallest church and commit yourself to being there for six months.” This was an unexpected and a quite surprising response that I felt, personally, very validating for my vocational journey. For a long time, I have felt called to a small congregation where the priority is on upholding one another in worship and in Christian love, not on programming the best church possible. A place where being community inevitably means committing to a place that includes people you maybe don’t like so much, the preaching and teaching may not be the best, and one must settle for whatever musical gifts people can offer.

So, moved by this response in the interview, I looked up Eugene’s number, called him up and asked to meet with him. To my surprise, he said, “Sure. What we normally do is meet at 11 am and talk for an hour to get to know each other. Then, we go to the Tamarac Brewery in Lakeside for lunch”. Again I was surprised. Not only did I get the privilege of meeting with the man, but I was going to get to drink beer with him too! He said that he was going to be traveling for the next couple of weeks so we scheduled to meet in the middle of November.

In the meantime, I looked up some of his books that I had never read. I most specifically was interested in inquiring about his perspective of those entering the ministry and asking his advice as a new pastor about priorities I should be setting at this early stage of my own ministry. I purchased and read through his memoir, The Pastor: A Memoir. It was fascinating stuff. He spoke about growing up in Kalispell as a Pentecostal, how his parents had both been pastors – his mom as a Pentecostal preacher to miners outside of Kalispell and his father as the butcher in town, how he himself never wanted to become a pastor because he thought they were all jerks growing up in the Pentecostal church, and how he kind of fell into his own ministry as a pastor just as he was about to enter his PhD program to become a professor. Instead, he started his career as a Presbyterian pastor, 29 years of which he spent pastoring the church that he and his wife, Jan, started in Maryland. From his experience of congregational ministry, I was most interested in the period of his life which he entitled “the Badlands”. When he and Jan moved to Maryland, Eugene started a church in their basement where they met and worshipped for 3 years while they were building their congregation and planning to build a church building. Then, after three years they were able to move out of the basement and into their very own church building. Almost immediately, attendance dropped off significantly. Eugene found that commitments among the members of the church community were not so much centered on encountering Christ in the midst of their Christian community as they were to the excitement of being part of a building project. When the building project came to an end, so did their commitment to the church. This took a toll on Eugene personally, and was something that I was interested in asking him more about.

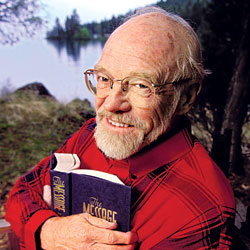

So, we were finally able to meet. I drove up and found his house. He lives right on the Flathead Lake with a gorgeous view of the Mission Mountains that I know and love so well. As far as retirement houses go, Eugene and Jan have a pretty sweet set up.

I was welcomed by Jan and Eugene quickly came to the door to greet me, as well. He graciously invited me in and we ascended the steps to his study. His study is filled with two great libraries. The west wall of his study, from end to end, is an array of books from literary, biblical, philosophical, and theological genres, in addition to many others. The east wall of his study is a library of a different sort – broad and tall window panes that enable Eugene to study the wonder of God’s creation in the magnificent Flathead Lake immediately beyond, with the towering Mission Mountains as a backdrop and the Big Sky as a cathedral ceiling. As a neophyte pastor, I felt dwarfed in my surroundings as we quietly took our seats across from one another.

We began by Eugene asking a little bit about me. I shared that I am a Lutheran pastor from Iowa and am married but do not yet have children. I shared where I went to school and seminary, and inquired a little bit about his background. I had read his memoir, The Pastor: A Memoir, and knew that he had grown up in the Flathead Valley to which he has now retired, but served much of his ministry out east in Christ Our King Presbyterian church in Bel Air, Maryland, that he and his wife were commissioned to plant on behalf of the church body. He shared that he loved it and believed that God called him there at the right time, provided for him during his time of call, and led him away at about the right time; 29 years after he started.

From his memoir, I was most intrigued by a period of time in his pastorate at Christ Our King which he referred to as his time in the “Badlands”. The Badlands, which he named after the Badlands area in South Dakota that he passed every summer on his visits home to Montana, was a time of frustration and spiritual purposeless that began in his third year of ministry. Since Christ Our King was a church plant, Eugene spent his first three years of ministry working to establish interest in the new congregation, grow the membership, and work towards plans of a new church building. This was an exciting time in which the congregation seemed to be discovering together who they would be as a church and what it meant for them to be members of the congregation. The congregation grew steadily during this time and they were able to build their own church building after three years. Everyone seemed really excited to have ownership in this new venture and their excitement continued until the new building was completed.

Then, once they finally had a building of their own, Sunday worship attendance dropped off dramatically. Eugene visited with several members who had not come for a little while and they expressed that they simply found other things to occupy their time and did not really feel bad that these competing interests now overshadowed their church attendance. Frustrated by this, Eugene sought out his mission director for advice. The director simply said, “Start another building project”. This further frustrated Eugene for it conformed almost too neatly to American consumeristic tendencies which hold that if we are not paying for something we cannot take ownership in it. The idea of simply being a worship community together, knit together in praise and adoration of God instead of by programs, strategies, or gimmicks, was a reality that his mission director advised against. And yet, this was a reality of congregational community that Eugene had sought from the beginning, so he looked for advice elsewhere.

He next sought out a Scottish Presbyterian pastor for spiritual direction. I had read about this in Peterson’s memoir, but I guess I did not grasp the full simplicity of his experience until talking to the man in person. He related that his meetings with this pastoral mentor were far more ordinary pastoral encounters than I would ever have expected to be inspirational and grounding for such a widely read theological voice as that of Eugene Peterson. He said that they would meet and sit across from one another in a cold, Reformed space. They would remain, sitting in silence for a time. Then, the pastor would read prayers from a Presbyterian prayer book for about 20 minutes to half an hour. Afterwards they would go get coffee and talk about other things. That was it! No profound discussions about the meanings of ministry or the failings of humanity. No elaborate rituals or passionate songs exchanged between them. No holy roller moments on the ground, extreme fasting, or any other dramatic spiritual practices that one might think of. Every week, they just sat quietly in a room together for a time, read prayers together, then left and got a cup of coffee. Fascinating!

After a couple of years of this, the Scottish fellow left for a faculty position so Eugene had to seek spiritual guidance from another source. He found it, oddly enough, in a nun. Their time of spiritual discernment and direction together was similar to what he had shared with the Scottish Presbyterian. They met on a weekly basis and read prayers together. He shared that they did not connect on quite the same level as he did with his first spiritual guide, but it worked for him. After six years of his time in the badlands, he one day realized that he was finally out of it. Six years of intentional sitting with a confidant in Christ, sharing primarily common prayers that were written down by others, led Peterson away from his time of frustration and purposelessness. This made the case to me that spiritual practices of obedient, regular prayer are very important in the Christian life.

Another highlight of our conversation together was when he shared his perspective on the importance of pastoral imagination. Walking from his study, I saw the new book Lila by Marilynne Robinson, the third book centered in the fictional town of Gilead. Having just finished the book, I commented that I appreciate Robinson’s work and inquired how he likes the book. He said that he and his wife Jan love to read portions of the book to one another aloud, and enjoy Robinson’s work very much. Later in our conversation, he came back to my mention of books I enjoy and he said, “I am glad that you read. It is very important in ministry to have a pastoral imagination.” I would be lying if I said that I did not feel a little bit of an ego boost to receive his compliment, but I was also very encouraged to understand the value that he places on what he deemed pastoral imagination. I have felt for a long time that creativity in ministry is important to many aspects of pastoral work, and I will remember his endorsement that reading fiction helps one think creatively and imaginatively about pastoral service to God and the church. To this end, he recommended that I read The Idiot by Fydor Dostoevsky. I have read and loved others of Dostoevsky’s work but not this one, so I intend to pick it up soon.

I also asked a few questions about his famous translation of the Bible, The Message. I first asked him if he ever expected it to be as popular as it has gotten. He responded, “Not at all. I thought [the idea of the book] was stupid”. I thought this was a very comical response to a work that has been incredibly popular and is now very important for many people in their devotional lives. I also asked him a question about the role of The Message translation in church life. I had once heard that he did not think that The Message should be read in public worship services, so I asked him whether that was true or not. (Our church uses the New Revised Standard Version, but I was just curious). I appreciated his response. He said, “No, I don’t think it should be read in churches. It is important for churches to share scripture and The Message was never intended for that.” What I think he meant is that it is important to have common texts with common translations that can be easily shared across church bodies and between denominations. The Message was translated for the audience of individual readers and private groups to read in their own study of the Bible, not to replace the translations that we already share as churches. I thought this was an important reflection on not only what he thinks about his own work, but also about how we read the Bible. There is no ‘one size-fits-all’ experience of scripture. We have both shared and individual approaches to the Bible; public, shared experiences of scripture, and private, personal readings of the Bible. Both are important and have different meanings for our lives that should not be pitted against one other, but held up together and appreciated for their differences.

All in all, I was very grateful for my meeting with Eugene Peterson. He is a pleasant, soft-spoken man who has had a good career full of meaningful work and experiences. I was glad for the opportunity to speak with him about them and hope to meet him again sometime in the future.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed